Call of the Wild

For years, those in the US looking for the opportunity to pet tiger cubs or snap a selfie with a lion or puma were able to pay-to-play with the animals at roadside zoos. These unlicensed facilities often keep animals in inhumane conditions and dispose of cubs when they become too large to attract visitors.

Thankfully, the practice is on the way out. In December, President Biden signed into law the Tiger King bill, named after the popular Netflix series that delved into private ownership of big cats. Under the new law, it is illegal for those without a license to own, breed, or transport big cats, including tigers, lions, leopards, cheetahs, and jaguars. Zoos and sanctuaries will still be able to breed and move the animals, but visitors won’t be allowed to touch them under any circumstances.

As Sara Amundson, president of the Humane Society Legislative Fund, told The New York Times, the law ends “a warped industry with no socially redeeming purpose, perpetrating great harm to animals while putting Americans at risk every day of the year.”

Those who already own big cats will be permitted to keep their felines under the new law, but they must register them with the US Fish and Wildlife Service or risk up to five years in prison or a $20,000 fine. They cannot breed or sell the cats, or acquire new animals. As privately owned cats pass away over the coming years, private ownership in the US will be phased out.

Free Flowing

As an increasingly warming world alters the water cycle, scientists have been woefully short on tools to measure just how much water is available and where it is moving. That’s about to change. A joint project between French researchers and NASA, the new $1.2-billion Surface Water and Ocean Topography satellite will provide constant updates on nearly all 6 million of the Earth’s reservoirs and lakes.

The SWOT satellite, which was launched in December, will estimate river flow rates and track the rise and fall of water in lakes and streams. It will refresh every 10 or 11 days. Until the launch of the project, water nerds were reliant on much smaller data sets: Current publicly available data exists for no more than 20,000 of the world’s lakes and reservoirs.

“We’ve never had measurements like this before,” Tamlin Pavelsky, one of SWOT’s lead US scientists, told Nature. “We don’t even have a baseline.”

More accurate flow rate measurements will improve our understanding of river hydrology. The satellite will also allow better understanding of how water circulates in the oceans. Rosemary Morrow, a French oceanographer and part of the project, likened the satellite to a new pair of glasses for a nearsighted person: “Suddenly everything comes into clarity.”

the big open

In late January, the Biden administration blocked the contentious Pebble Mine, citing the need to protect Alaska’s Bristol Bay and “the jobs and communities it supports.” The administration used a rare veto invoked under the Clean Water Act to halt the mine, whose disposal material from construction and operation, it said, “would destroy 100 miles of streams and more than 2,100 acres of wetlands.”

Agency officials said they followed a sound-science approach and were disregarding an Environmental Impact Statement from the Trump administration that was not thorough in assessing likely impacts of the mine.

“Bristol Bay is an ecological treasure and an economic powerhouse that feeds the world,” Collin O’Mara, president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, said in a statement following the decision. “Building a mine in this pristine system will never make sense.” The decision will protect the largest sockeye salmon run in the world and support some 15,000 jobs and $1.2 billion in economic output, the group said. It will also help protect the traditions of the Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq peoples.

The veto was part of a string of pro-environmental decisions made by the Biden administration in January that environmental and Indigenous groups had long been pushing for.

Earlier in the month, administration officials banned logging and road-building in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, protecting old Sitka spruce and habitat for salmon, eagles, and bears. It also set a 20-year mining moratorium upstream from the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, halting a bid for a proposed copper and nickel mine while furthering protection for 225,000 acres of watershed.

Environmentalists are hoping the administration’s green streak will extend further and lead to the cancellation of the Willow Project — a proposed massive oil terminal and drilling platform in the sensitive Alaskan Arctic.

TEMPERATURE GAUGE

This one’s a bit of a head-scratcher: Apparently, when natural disasters hit, home prices go up. At least that’s been the pattern in hurricane-ravaged Florida.

According to new research published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, between 2000 and 2016, home prices in Florida neighborhoods impacted by hurricanes were five percent higher in the three years following a storm than prior. While prices returned to pre-storm levels after three years, they didn’t drop lower. And by the time they stabilized, neighborhoods had gentrified: Three years after a hurricane, more than 25 percent of homes were occupied by households with higher incomes than before the storm.

“Our findings show that the idea that people will naturally retreat from hazardous areas may not necessarily hold up,” Yanjun (Penny) Liao, one of the study authors and a fellow with the nonprofit Resources for the Future, said in a statement.

The researchers relied on housing information from the real estate website Zillow, state tax assessments, and NOAA hurricane data for their study. While they aren’t sure about what’s causing the post-hurricane price spikes, they have a few ideas. For one, there’s a decrease in housing supply following storms, given the property damage they cause. There’s also the fact that wealthier people can better afford to live in high-risk areas — they can pay higher home insurance premiums or can pay out-of-pocket for repairs that insurance won’t cover.

“In some ways, this indicates a market flaw given the current state of the climate,” says co-author Joshua Graff Zivin, an economics and global policy and strategy professor at the University of California, San Diego.

The research also expands our understanding of what climate gentrification may look like: As hurricanes and other extreme weather events become more frequent and intense, wealthy households may increasingly displace lower-income ones both as they flee to more climate-safe locales and as they move into climate-vulnerable neighborhoods.

FRONTLINES

Bell Laboratories’ sustainability webpage is filled with nature photographs, and a brief scroll provides links to conservation projects, environmental awards, and “green” pest control products. But while the company, which is “an exclusive manufacturer of rodent control products,” appears to promote an image of environmental consciousness, according to a recent lawsuit, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

In January, the nonprofit Raptors Are the Solution (RATS) filed suit under Washington DC’s Consumer Protection Procedures Act, alleging that the Bell Laboratories’ sustainability claims are misleading. The lawsuit argues that through use of terms like “sustainable,” hashtags like “#earthfriendly,” and descriptions of products as “low risk,” Bell Laboratories suggests to consumers that its products are green. In reality, many of its rodenticides contain active ingredients — including blood thinners — known to cause painful deaths in target species, as well as death and illness in non-target animals like foxes, coyotes, and birds of prey.

“It’s bad enough that their poisons are killing and sickening so many animals, but to mislead consumers by telling them their poisons are ‘sustainable’ is completely unacceptable,” says Lisa Owens-Viani, director of RATS. (RATS is a project of Earth Island Institute, which publishes the Journal.)

The impact of rodenticides on both target and non-target animals is well documented. Animals can be exposed by ingesting the poisons directly, or by consuming other animals who have ingested them. “I think consumers expect honesty in advertising from companies,” says Sumona Majumdar, general counsel of Earth Island Institute, who helped file the lawsuit. “And I do not believe consumers are aware that the products manufactured by Bell Laboratories have such horrific impacts not only on the target species, but on wildlife and even their pets.”

Findings

The northeastern tip of Greenland is a harsh polar desert region with vast open spaces, snow-covered mountains, few trees, and sparse wildlife. Nothing in the landscape offers even a hint that this land once held lush forests of willow, birch, poplar, and cedar trees, where mastodons and the ancestors of caribou roamed. But so it was, says a study published in Nature in December.

Researchers analyzing two-million-year-old DNA sequences from a fossil-rich rock formation in the northernmost reaches of Greenland have found evidence of 102 different genera of plants, including 24 that had never been found fossilized in the formation, and nine animals, including horseshoe crabs, hares, geese, and mastodons.

That was “mind-blowing,” because no one thought mastodons ranged that far north, Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Cambridge and senior author of the study, told Scientific American. “What we see is an ecosystem with no modern analogue.”

The researchers reconstructed what this region, known as Peary Land, would have looked like back then using fragments of DNA — basically cellular material shed by living things via skin, excrement, etc. — recovered from the environment and comparing them with genomes of modern species. Based on their analysis, they say the region was once a forested coastline where a river flowed into an estuary. The river carried DNA fragments from land into the marine environment, where they were preserved. That’s why the researchers found evidence of horseshoe crabs and coral alongside DNA from caribou, ants, fleas, and lemmings.

Studying the genetic sequences of these ancient animals could reveal adaptations that could help Arctic species survive as the climate changes once again, Willerslev says.

In Memoriam

In December, wildlife officials in Southern California euthanized a 12-year-old mountain lion we had named P-22. The big cat was a much-revered figure in the land of the famous, having survived a delicate cohabitation with humans, trapped as he was amid the coastal woodlands of the Hollywood Hills. He was captured because he had turned to predation on Chihuahuas, a sign that he was getting too old and too tired to hunt deer.

Medical tests then revealed that P-22 had “significant trauma” to his head, right eye, and internal organs, most likely from being hit by a vehicle. The tests also showed pre-existing illnesses including kidney disease, chronic weight loss, a parasitic skin infection, and arthritis. The mountain lion’s “clear need for extensive long-term veterinary intervention left P-22 with no hope for a positive outcome,” the California Department of Fish and Wildlife said in a news release announcing the decision to euthanize him.

All life is precious, and one ought not make a symbol of what is called “charismatic megafauna.” But it is hard not to see P-22’s ignoble demise as symbolic of a greater diminishment. As humans hurl through the twenty-first century, devouring wild spaces, wiping out birds, parching rivers, and bleaching reefs, news of a specific loss, like that of P-22, hits hard. We should understand these moments as calls to action, to do better, to think harder about our relationships to our wild kin, and do what work we can, wherever we can, to keep them.

Here is how we can honor P-22: Remember him roaming the dark hills, hunting beyond the city lights, forever free in our collective imagination, which needs all the wild it can hold.

Frontlines

Though the United States has an abysmal human rights record where protesters are concerned, its environmental activists had, until recently, avoided the fates of hundreds like them in other countries who have been killed by authorities. That changed in January, when police shot to death an activist protesting the destruction of the South River Forest outside Atlanta, Georgia, to make way for a $90-million police-training center.

Police claim they killed Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, better known as Tortuguita, after he shot at them — a claim fellow activists and family members dispute. The killing marks a dangerous turning point for activists, who have in recent years seen their rights to assemble and protest diminished by state laws. It is part of an ongoing pattern of civilian killings by police nationwide, who enjoy immunity from civil suits and who have become increasingly militarized in recent decades.

THE FOREST & THE TREES

Trees and plants regrow, so surely they are a renewable energy source, right? That has long been the argument of the biomass industry, one that many countries, including the US, UK, Canada, and Japan, as well as the European Union, have bought into as they scramble to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels. Many are ready to harvest wood from their forests or import wood pellets from overseas for biomass-fired power plants, despite solid research showing that biomass burning releases more carbon dioxide emissions per unit of energy produced than coal, and forests can take decades or even up to a century to regrow and draw the same amount of carbon back out of the air.

Now, thanks to relentless campaigning by environmentalists, at least one country might finally be taking off its blinders.

In December, Australia, the world’s 13th largest economy, reversed its renewable classification of woody biomass energy, declaring that wood harvested from native forests and burned to produce energy cannot be classified as a renewable energy source. It is the first major global economy to make such a call. The decision came as two big power stations in Queensland were on the verge of switching from coal to biomass, and several other coal plants in Victoria and New South Wales were considering it as well, Mongabay reports.

Around the same time, following an investigation by Mongabay that revealed that Enviva — the world’s largest maker of wood pellets for energy — was contributing to deforestation in the US Southeast, The Netherlands said it would stop paying subsidies to any biomass company found to be untruthful about its wood-pellet production methods. The Netherlands, which like the rest of EU nations classifies woody biomass as renewable, currently offers sizeable subsidies to Enviva.

These two decisions pose the first significant setback to the biomass industry at a time when pellet production is scaling up in the US Southeast and British Columbia in order to supply growing demand in Europe and Asia.

Findings

The Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) sounds, based on its name, like an organization with a positive mission. Ending plastic waste is a widely shared goal these days, after all. But upon closer inspection, it turns out the nonprofit is an industry-sponsored group.

A recent investigation by Bloomberg Green revealed that AEPW is dominated by petrochemical companies that are steering the organization — and the global conversation — away from efforts to reduce plastic production. Nine of the 15 members of the organization’s executive committee are petrochemical giants — including Exxon Mobil, Dow Chemical, and Chevron Phillips Chemical — and two are plastic-packaging producers. Unsurprisingly, its efforts to address plastic have so far been miniscule.

Four years into its operations, the organization says it has diverted 34,000 tons of plastic waste. That’s just 0.2 percent of its five-year goal to remove 15 million tons. Meanwhile, member companies are selling a whole lot more plastic than AEPW is diverting from the environment. The group is also actively pushing against efforts to cap plastic production, saying it would “hinder progress towards a more sustainable, lower-carbon future.”

“It’s actually quite sophisticated greenwashing,” John Willis, director of research at the think tank Planet Tracker, told Bloomberg. “The big oil and chemical companies are basically saying, ‘Don’t go near production, just focus on the downstream recycling — reuse, recover — because we’re not to blame.’”

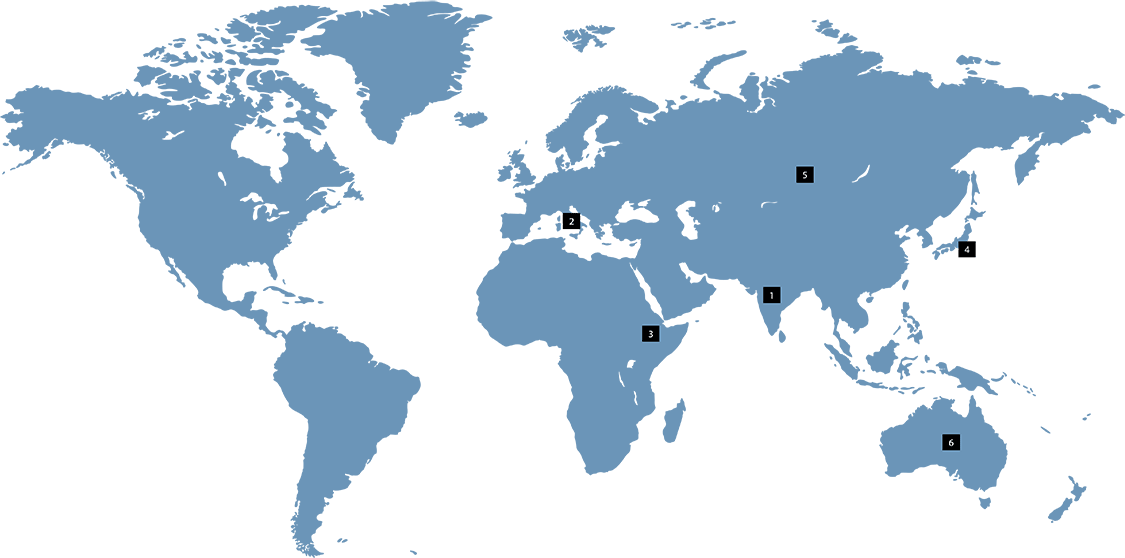

Around the World

Formally protected areas are often seen as the cornerstone of conservation work. Safeguarded under the law, they offer essential refuge to the plants and animals living within their bounds and a line of defense against the biodiversity crisis unfolding all around us. But they are hardly the only — or earliest — type of land conservation. Long before we had legally protected spaces, we had sacred natural sites.

Believed to be the first form of habitat conservation in human history, sacred natural sites are areas of land or water with special spiritual significance for people, especially Indigenous communities. Found around the world, they are most commonly small groves or patches of forests, but they also include islands, rivers, mountains, and more. Some have been protected for millennia.

In addition to their spiritual significance, sacred natural sites have long been recognized as hotspots of biological and cultural diversity, and as important sources of medicinal plants and clean water as well. As Piero Zannini, a professor at the University of Bologna and author of a 2021 review linking sacred natural sites to positive conservation outcomes, told Yale360, “They are becoming ever more important as reservoirs of biodiversity.”

There are likely hundreds of thousands of sacred natural sites around the globe, many of which face increasing threats from humans. Here are a handful of the places where they continue to foster a deeper relationship between people and nature while sheltering vulnerable plants and animals.

Sources: Biodiversity and Conservation, Global Citizen, Change.org, Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture, Scientific American, Yale360

1 India

In addition to sacred lakes, waterfalls, rivers, and caves, by some estimates, India is home to as many as 150,000 sacred forest groves alone. These groves are known to protect original forest cover, have higher biodiversity, and even contain some of the last remnants of certain forest types in some regions. Safeguarded for generations for both their spiritual and practical value, many of these forest patches are now being uprooted for new developments, including for solar arrays in Northeast India.

2 Italy

Conservation may not be the first thing that comes to mind when most people think of Christianity, but in Central Italy at least, the Catholic Church has served as a force for nature protection. There, researchers have described sacred natural sites — including small chapels, large temples, and shrines — as “one of the most important biodiversity hotspots in Europe” for their high plant diversity and endemism.

3 Ethiopia

The last fragments of Afromontane forests in the highlands of southern Ethiopia can be found in some 20,000 small “church forests” that surround Ethiopian Christian Orthodox Tewahedo churches and monasteries. Over the past five decades, many of these forests — which are used for religious ceremonies, burial grounds, and community gatherings — have managed to expand, even as the agricultural land surrounding them has suffered desertification and state- and community- managed forests have degraded.

4 Japan

Shinto shrines cover more than a quarter-million acres in Japan and contain virtually all of the country’s remaining lowland forests. Some of these forests were initially preserved to supply wood for temple construction. In addition to its Shinto forests, Mount Fuji, too, has for centuries been revered as sacred in Japan. First ascended by a Buddhist monk in the twelfth century, the mountain, however, now bears the burden of hundreds of thousands of annual climbers and the waste they leave behind.

5 Altai Republic, Russia

The Karakol Valley is home to a multitude of sacred sites for the Indigenous Altai people, as well as to rare and vulnerable plants and animals, including the snow leopard, black stork, and demoiselle crane. Protection of the valley is essential to maintaining the Altaians deep connection to nature. To that end, they have set up a formal park to help safeguard the cultural and natural heritage of the region, which currently faces threats from international tourism, development, and infrastructure projects, including a natural gas pipeline.

6 Australia

Sacred groves can be found across the Australian landscape, from the country’s coastal rainforests to its arid interior woodlands. In Victoria, some of these groves are at risk of being felled. The state has proposed cutting down hundreds of trees sacred to the Aboriginal Djab Wurrung women, who have used some of these as birthing sites for 50 generations. The reason? A highway upgrade. At least one centuries-old tree has already been lost. The fate of the others rests in the hands of the legal system as locals attempt to stop the project.

HIGH VOLTAGE

Humans have less than 30 years to cut their carbon emissions to net zero, or we face dire climate consequences. But the International Energy Agency is warning that the race toward a renewable future could have major stumbling blocks. That’s especially true for minerals and their markets. Clean energy technologies require more copper, nickel, lithium, and other minerals to build — a lot more — than their current counterparts.

“Since 2010 the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50 percent as the share of renewables in new investment has risen,” the IEA says in a recent analysis. To keep global temperature rise below a 20C threshold by 2040, mineral requirements will quadruple, the IEA says. “An even faster transition, to hit net-zero globally by 2050, would require six times more mineral inputs in 2040 than today.”

The 100,000 tons of minerals needed, however, are paltry compared to the tonnage of fossil fuels currently pulled from the ground to sustain our society.

TABLE TALK

One of our most hardworking pollinators, honeybees have been facing multiple threats in recent years, including habitat loss, pesticide pollution, climate disruption, and attacks by persistent pathogens. But now there’s a bit of good news for them: The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) recently approved the world’s first-ever honeybee vaccine.

Developed by the biotech company Dalan Animal Health, the vaccine helps bees fight off American foulbrood, a highly contagious bacterial disease that turns bee larvae into brown goo and can wipe out entire colonies. Until now, the only treatment for American foulbrood, which originated in the US and has since spread across the world, involved laborious applications of expensive antibiotics, which had limited effectiveness. Beekeepers are often forced to burn infected hives and bees to stop the spread.

The new vaccine, which contains a dead version of Paenibacillus larvae, the disease-causing bacteria, is much easier to use: It can be mixed into the food that worker bees eat. When the worker bees secrete their milky royal jelly for the hive queen to feed on, the vaccine gets deposited in her ovaries, where it immunizes developing larvae.

In a statement released in early January, Dalan said the breakthrough could be used to find vaccines for other bee-related diseases, such as the European version of foulbrood. It also said that since the vaccine is not genetically modified it can be used in organic farming.

Dalan currently has a conditional, two-year license from the USDA and plans to initially distribute limited amounts of the vaccine to commercial beekeepers, and offer it for sale across the country later this year.

The vaccine could be a huge deal for US agriculture, which is heavily reliant on managed honeybee colonies. According to the USDA, honeybees pollinate 80 percent of all flowering plants in this country, including more than 130 types of fruits and vegetables. Bee pollination accounts for about $15 billion annually in added crop value.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.