In 2003, a barn own with a severely damaged wing was brought to the attention of Sarah Higgins, an environmentalist living by Lake Naivasha in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley. The owl had been brought to the vet but the wing did not heal correctly, which meant the bird could not be returned to the wild. So she built an owlery in her garden and named the owl Fulstop. Thus began the Naivasha Owl Center, one of only two places in Kenya that rehabilitate sick and injured birds of prey. Today, the Center is licensed for avian care by the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), the government agency that manages the country’s wildlife, and Higgins is an honorary KWS warden.

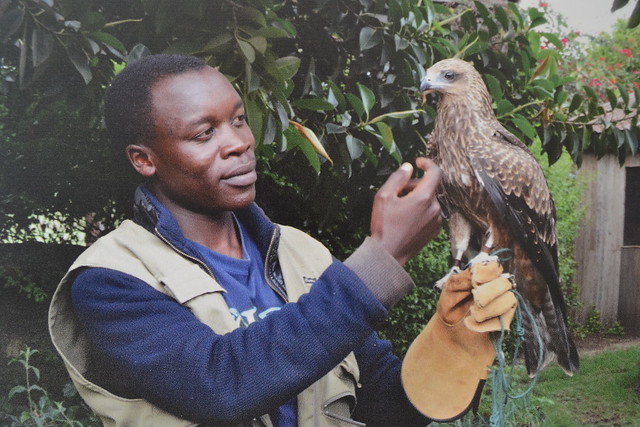

Photo courtesy of Naivasha Owl Centre Falconry techniques are used to rehabilitate raptors at the Naivasha Owl Centre, one of only two such centers in Kenya that treat birds of prey.

Photo courtesy of Naivasha Owl Centre Falconry techniques are used to rehabilitate raptors at the Naivasha Owl Centre, one of only two such centers in Kenya that treat birds of prey.

Birds come to the center after sustaining injuries in the wild or because of harmful interactions in populated areas. Three young spotted eagle owls — called Snap, Crackle, and Plop — were rescued after being swept out of their nest on a quarry wall during a rain storm and tumbling down. Two of them sustained broken wings, but all three are now healed. They make clicking sounds of warning if you come too close.

Garfunkel is a Lappet-faced vulture that ate poisoned meat intended for lions suspected of killing cattle. He recovered from the poisoning, but had also been bitten in the wing by a jackal at the same carcass and is still healing. An African fish eagle named Baringo was rescued near Lake Baringo in the Rift Valley and transported to the center by KWS staff, who are not equipped to give specialized avian care.

And it’s not all raptors. At the moment, the center is also caring for a migratory white stork and a rather aggressive pelican that lost a wing to a powerline.

From its early days with just the one owlery, the center can now house 65 birds. There’s also an onsite hospital with an operating theater and recovery room. When birds are brought in, they receive veterinary care, proper feeding, and rehabilitation training to prepare them for a return to the wild.

Basic falconry techniques are used to exercise the birds and build up their flight muscles. On the day of my visit I found a falconer wearing a large yellow glove and training some Yellow-billed kites. A pair of Augur buzzards and a young fish eagle were standing on falconry perches awaiting their turn. Higgins exercises the younger owls each day in a long flying area enclosed in a mesh fence, using live mice to teach them how to hunt.

When the larger raptors regain fundamental bird skills, they are taken for further hunting training at the Soysambu Raptor Camp, the other bird rehab center in Kenya, which is run by the Simon Thomsett, Kenya’s foremost expert on raptors. Once birds are assessed as both flight-fit and proficient at hunting they are released. “Without being certain of these criteria, releasing any bird will consign it to a long, agonizing death due to starvation,” says Shiv Kapila, a raptor enthusiast and bird trainer at the Center.

Photo by Kari MutuTai, a large Verreaux’s eagle owl with huge black eyes and pink eyelids, was found

Photo by Kari MutuTai, a large Verreaux’s eagle owl with huge black eyes and pink eyelids, was found

near the Kenyan coast. He lives permanently at the Center because, as Higgins

puts it, “he doesn’t know how to be an owl.”

In 2015, Higgins, Thomsett, and Kapila formed the Kenya Bird of Prey Trust in order to pool their knowledge and expertise regarding raptor care and restorative management. The Trust identifies diverse regions in Kenya that are suitable for release of rehabilitated raptors, which are acclimated to the wild through a weeklong process of that ensures each bird can successfully hunt in its new home. Different habitats and conditions are required for different species. For example, territorial birds, such as fish eagles, can only be introduced into an area without others of their kind or else a deadly fight will ensue.

Not all birds can be released in the wild. Some remain at the Center permanently because they do not fully recover, and so they become ‘teaching birds’ to help visitors learn about birds of prey. One such resident is an augur buzzard that was given the wrong food by its former owner and never developed the primary feathers that are crucial for flight.

Unfortunately, less conservation attention is paid to birds of prey compared to Africa’s big cats and large herbivores like elephants and rhinos. Yet raptors exhibit some incredible behaviour. “Martial and crowned eagles regularly kill large antelopes the size of impalas and bushbuck. Peregrine falcons have been recorded swooping on their prey at 275 mph,” says Kapila, who is also a freelance safari guide.

Additional attention is much needed, especially for African vultures, which are in a dire situation due to habit loss, inadvertent poising, and harvesting of their body parts for traditional medicine. Six of the eleven African vultures are at high risk of extinction according to the IUCN Red List. (Read more about why vulture populations in Africa are declining.)

Other raptors are targeted by farmers concerned that they’ll snatch chicks and small livestock. And birds of prey often fall victim to rodenticides set out to kill mice.

Other species face cultural hurdles. For example, in Kenya superstitions still prevail around owls because of their nocturnal activity, soundless flight, and ability to turn their heads around to see behind them. Some communities believe that if an owl stands on the rooftop and hoots, it means that somebody in the home will die.

Thomsett believes it is imperative to involve the African public and landowners in bird protection. “We should entrust citizens from all walks of life, and with whatever skills they have, to work together. Otherwise we will lose more raptors.”

Consequently, creating awareness about birds of prey is part of the wider conservation mandate of the Trust. Staff from the Center regularly visit local schools to talk about the importance of birds, to stop the persecution of raptors, and to dispel “the unfounded conviction that every bird of prey will definitely kill their chickens,” Higgins says, adding that as a result of this outreach there is now a huge demand for school visits.

Aready, the Trust’s public outreach efforts have succeeded in turning around some attitudes towards birds. “We have had several calls from the schools in the areas that we have visited to come and rescue an injured or sick bird,” Higgins reveals.

In the long-term, the Trust hopes to establish a visitor center so that more students and other visitors can come to learn about birds of prey. And Higgins says more could be achieved if the Trust were better supplied. There’s a shortage of qualified avian vets in Kenya, for example, and a need for more operating equipment and an X-ray unit so that vets can work on site Naivasha Owl Center. As it is, the Trust often has to transport injured and traumatised birds over long distances for care.

In the meantime, the Center will continue caring for as many birds as it can — it has already treated some 290 — and Fulstop, the first barn owl Higgins rescued, will maintain his perch in the owlery.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

Donate