Last March, a frontpage story about a proposed biomass power plant appeared in my local newspaper, The Transylvania Times. Matthew Ross, an attorney representing the plant’s business owners, Renewable Developers, told the reporter that the $22 million, 4-megawatt facility could put our little county in the mountains of western North Carolina “at the forefront in the race toward fossil-fuel independence.” He said the plant’s cutting-edge pyrolysis technology is quickly emerging as a safe source of renewable energy. “The process is an extremely clean, state of the art gasification system that will convert the raw feed stock, MSW [municipal solid waste] and wood waste into a synthetic gas that closely resembles natural gas,” Ross assured the reporter. “It bears absolutely no resemblance to incineration.”

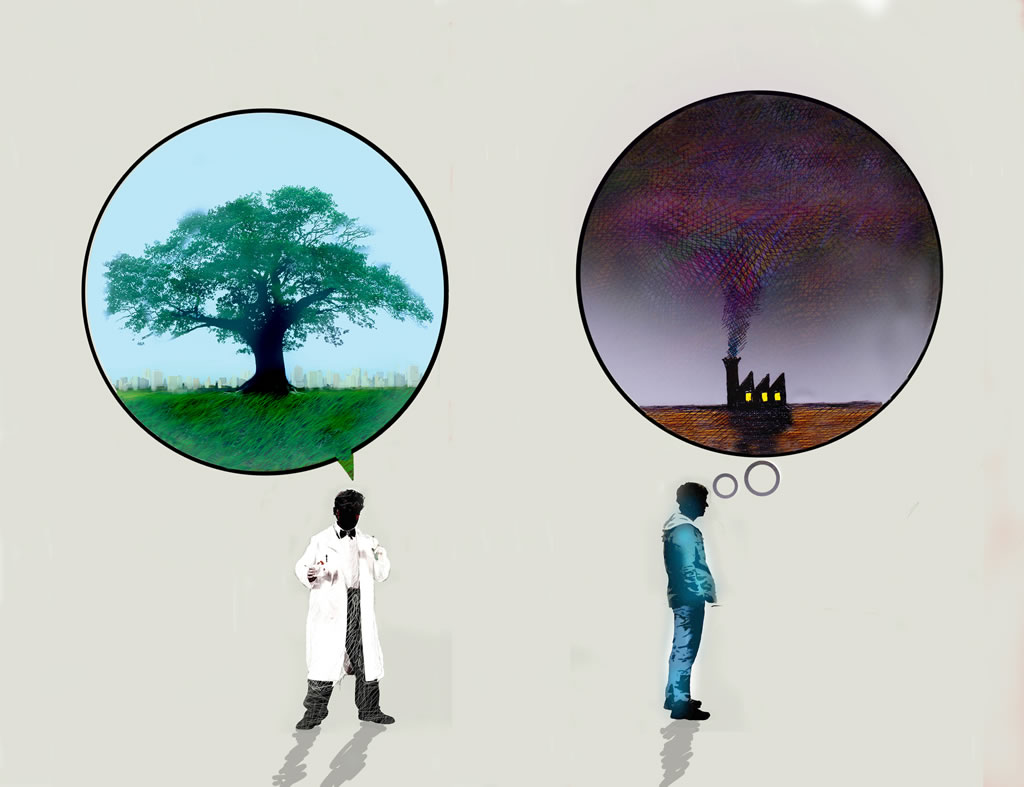

Illustration Gary Waters

Illustration Gary Waters

To many people around here, this sounded like an attractive opportunity. Transylvania County has fallen on hard times since its two major factories shut down in 2002; two-thirds of the children in the public schools now qualify for free lunches. Our predominantly right-wing politicians have been trying hard to lure some kind of decent-paying industry back to town, and at least some of them appeared to believe that this biomass plant could finally be the answer to their prayers.

But some other local citizens had different ideas. Shortly after news about the proposed biomass power plant became public, they created a Facebook page, “The Transylvania County Biomass Info Exchange,” and a group called “People for Clean Mountains.” Communicating through these online channels, a rapidly expanding group of people soon posted hundreds of articles and links that challenged Ross’s case for the project. A grassroots opposition movement began to gain force.

In April, a month after the newspaper article appeared, Ross delivered a 45-minute PowerPoint presentation at the local library to a standing-room only crowd of several hundred people. Many of those in the crowd were wearing blue to show their support for People for Clean Mountains and their resistance to the plant. During a follow-up Q&A, one person after another stood up and blasted Ross with arguments against the proposal. When the verbal bloodbath finally ended, everyone stood up and stormed out.

In a way, the community forum at the library was inspiring: Here were citizens engaging passionately in an important civic issue. But as I drove home through the rainy night in my gasoline-powered car to my inefficient, coal-powered home, I was uneasy. I myself felt deeply conflicted about this project. Despite all its substantial flaws, was it nevertheless a baby step in the right direction toward a greener economy? I wondered whether what I had just witnessed was an exemplary display of enlightened grassroots environmentalism, or self-righteous, manipulative, and cynical NIMBY-ism.

After the event, Ross told Transylvania Times reporter Eric Crews that while he had expected to hear some concerns at the meeting, he was surprised by the “angry and vitriolic” tone, and found the lack of substantive, reasoned dialogue “very regrettable.”

“They basically called Ross a liar,” Crews told me. “They didn’t give him an opportunity to make his case or respond to their questions. As a reporter, I strive to remain neutral, but it seemed to me that people were unfairly lumping together pyrolysis and incineration, and that a lot of the scientific papers they were citing on PCM’s website and Facebook exchange were dated and not necessarily relevant to this project. I felt like they were just trying to use ‘science’ and ‘environmentalism’ to stop something they didn’t want in their backyards.”

While writing an earlier article about this project, Crews had called me to ask whether, as an environmental science professor, I supported the biomass plant. I appreciated Crews’ good intentions; he was doing exactly what a good reporter should do, trying to find a reputable source who could provide unbiased analysis. Still, a part of me wanted to respond flippantly and say, “We don’t ask political scientists who they will vote for in the next political election, so why ask environmental scientists which side they will support in a big environmental decision?”

I didn’t say that, though, since I already knew the answer. The reason we ask scientists such questions is because we believe that science is rigorous and objective. We believe that science seeks, and ultimately discovers, the plain and unadorned truth. Science sits on a higher plane, far above the muck of politics and the constant swirl of culture.

Of course, not everyone believes these things. There’s a deep current of anti-intellectualism running through American society. You can trace a straight line from the Scopes Monkey Trial more than a century ago to today’s Creation Museum, where children are told that Adam and Eve co-existed with the dinosaurs. “Prepare to Believe,” reads the tagline of the Creation Museum, and for millions of Americans, belief – or faith – will always trump science.

But the popular commitment to scientific empiricism is just as strong, if not stronger. And so, when it comes to public policy making, we often hear that we should base our decisions on “the best available science.” Want to know how to reform our education system? Look at what the studies say. Want to improve our health care system? Examine all the research on the subject. We are happy to place ourselves at the mercy of “experts.” The fervor for science-based decision making at times resembles religious fundamentalism – only it’s a secular fundamentalism, one that replaces God with Reason.

The bias toward science’s infallibility is common among political liberals in general, and environmentalists in particular. Partially this is because – since the days of George Perkins Marsh and John Muir – an ecological worldview has been founded upon an understanding of (or at least an appreciation for) the earth sciences. An esteem for science in embedded in environmentalism’s DNA. For evidence of this, look no further than the continuing controversy over global climate change. Many environmentalists think that if only they could cut through all the propaganda and junk science paid for by the fossil fuel interests, and show the masses the unassailable scientific evidence for anthropogenic global warming, then we could break through the logjam and start solving the problem.

That’s just magical thinking. There is no such thing as a completely objective scientist or completely objective science.

We might like to believe that there are some cold, hard truths out there, and that pure science is the best way to discover and disseminate those truths. The irrefutable laws of physics and chemistry will rise above our petty politics and guide our way forward. But the comforting image of scientists marching toward the true laws of nature is a myth. The real cold, hard truth is that such “laws” are merely ever-evolving human constructs. And the interpretation of those constructs is always subject to debate. As the fight over one biomass power plant in the mountains of North Carolina was making clear, everyone believes “the science” is on their side.

I, too, was convinced that science was on my side when I set out to save the world as a conservation biologist fresh out of graduate school. But I soon learned that, regardless of our politics or our professions, we all love to argue for “science-based solutions.” Until, that is, the said science suggests something we don’t like. Even in the rare instances in which I managed to get a group of opposing stakeholders to agree to resolve their differences by deferring to “the science,” they almost always disagreed over how to choose, interpret, and apply this science in the messy real world.

Even within academia, scientists self-select into ideological disciplines. For example, scientists who, like me, choose to study ecology and conservation biology tend to have fundamentally different perspectives and values than those who choose physics or chemistry. Physicists and chemists are reductionists; ecologists are more likely to be holistic systems-thinkers. While ecologists are generally less enthusiastic about technologies such as nuclear power and GMOs, many physicists and chemists are in favor of them. Whether we are aware of it or not, the details of our personal and professional lives also profoundly affect how we do our own science, interpret the work of our colleagues, and ultimately decide what to support and oppose. In other words, scientists turn out to be just like everyone else.

Having been indoctrinated into the Church of Science somewhere on my way to earning a PhD, the notion of science as unavoidably biased and subjective seemed at first like blasphemy. But my repeated failures to resolve environmental conflicts with science ultimately led me to explore the work of political scientists and social psychologists. I discovered that “scientizing” conflicts in general – whether it’s climate change or the Bush/Gore Florida recount – tends to lead to both greater intellectual uncertainty and more intense political polarization.

Daniel Sarewitz, a DC-based researcher who co-directs Arizona State University’s Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes, has done some of the best work in this field. As he succinctly stated in a 2006 article published, ironically enough, in American Scientist: “Even when a disagreement seems to be amenable to technical analysis, the nature of science itself usually acts to inflame rather than quench the debate.…‘More research’ is often prescribed as the antidote, but new results quite often reveal previously unknown complexities, increasing the sense of uncertainty and highlighting the differences between competing perspectives.”

In a previous paper, Sarewitz illustrated this phenomenon by examining the shifting science and politics associated with the proposed US nuclear waste site at Yucca Mountain, a 230-square-mile section of Nevada desert that is probably the most thoroughly studied chunk of real estate on the planet. The hydrological system is a critical component of the suitability of any potential nuclear waste site because flowing water may accelerate the degradation of the waste containment vessels. Initial estimates in the early 1980s of the rate at which water flows through rock at Yucca Mountain indicated a percolation flux of between 4 and 10 mm per year. Further research reduced these estimates to between 0.1 and 1 mm per year. By the mid-1990s, this technical issue was considered more or less settled. Then persistent political pressure forced the government to conduct new hydrological research utilizing different techniques. This, in turn, led to the conclusion, based on an aggregation of estimates from seven outside experts, that the percolation flux at Yucca Mountain was actually somewhere between 1 and 30 mm per year.

Sarewitz points out that the first wave of research at Yucca Mountain was sponsored by the Department of Energy, an agency with strong institutional motivations to keep the project moving forward. As the research opened up to a greater diversity of scientific and political players, a correspondingly greater diversity of perspectives and approaches came into play. The final result – after decades of research funded by billions of taxpayer dollars – was a higher level of uncertainty. Ironically, not long after promising in his first inauguration to “restore science to its rightful place,” President Obama slashed funding for Yucca Mountain, effectively killing the project for blatantly political reasons.

In a recent conversation, Sarewitz told me that two things impressed him when he went to Capitol Hill on a postdoctoral congressional science fellowship in 1989: “The first was the capacity for politicians to mobilize legitimate experts on different sides of the issues to debate each other. The second was how some of the people I completely disagreed with philosophically, intellectually, and ideologically were good, smart people who brought a rational and credible perspective to the table.”

“Science is permissive of all sorts of things,” he continued. “If you find the science that supports what you want to do, then you think it can dictate what everyone else should do, and you don’t have to be honest about the complex sources of your own motives. On the other hand, if someone tells us the science says we have to do something we think is wrong, of course we don’t trust the science! So in these sorts of complicated mixes of science and politics, the idea that scientists can act as experts dictating particular policy choices divorced from their personal worldviews and values is bullshit.”

There’s a technical name for this all-too-human behavior: “confirmation bias,” which is our tendency to find evidence that supports our beliefs and discard the evidence that challenges them. The old-fashioned term is “cherry-picking.” Each side in a dispute has no problem rounding up a scientist or two who will confirm its original position. And – in yet another irony – cherry-picking is usually the sin of your political opponent. Liberals can enjoy Chris Mooney’s The Republican War on Science, while conservatives can dig into Alex Berezow and Hank Campbell’s recent rejoinder, Science Left Behind: Feel-Good Fallacies and the Rise of the Anti-Scientific Left.

Seasoned environmentalists understand the challenges posed by confirmation bias. “Picking and choosing science is a common problem,” says Bruce Hamilton, the deputy executive director of the Sierra Club. “Everybody’s got a scientist and some science on their side. So at the end of the day, the science doesn’t resolve the issue.”

Tina Swanson, the director of NRDC’s Science Center, told me: “Even when you have the best possible science that is completely unquestioned and incontrovertible, getting change implemented is slow and incremental. There are other drivers that are often closely intertwined with the science, such as societal values, economics, and the technical and political feasibility of what you want to do.”

And yet appealing to the authority of science as a kind of trump card is a hard habit to break. It only takes a few minutes of Googling to find plenty of Sierra Club press releases or NRDC blog posts with some version of “according to scientists.” The more complex and dire our environmental problems become, the more we seem to view science as a magic wand that can make disputes disappear. We want blue ribbon panels of dispassionate scientific priests to tell us what to do and save us from ourselves.

There are three major problems with this admittedly appealing fantasy.

First, if and when “the leading scientists” agree with each other, history has shown that they are often wrong – or at least not any smarter or wiser than the rest of us. In addition to the undemocratic nature of putting an elite group of scientists in charge, the track record of “science-based” policies has been mixed, at best; the embrace of infant formula and DDT in the mid-twentieth century are just two examples of such scientific missteps. And when scientists get tangled up with powerful interests, they can be used to legitimize some horrific ideas, such as the “science” of eugenics.

“It would be a lot more constructive if we could argue about values instead of facts.”

Second, highly trained and credentialed experts often sharply disagree with one another. Consider the radically different judgments typically handed down by our Supreme Court Justices after hearing the same learned arguments over the same Constitution. Our most venerable scientists often reach equally divided conclusions because they are similarly informed and motivated by a complex mixture of rationalism, emotion, values, self-interest, and ego. In short: scientists are people, too.

Third, asking scientists to solve a complex problem like climate change is as misguided as asking architects to solve homelessness. This is because – despite its undeniable power and achievement – science is merely a tool. Like any tool, science is very good at some things and very bad at others. One of the things that science is not good at is resolving our underlying political and philosophical differences.

“It’s very difficult for environmentalists to use science to persuade others to support something,” says Dan Kahan, a professor of law and psychology at Yale, and a member of Yale’s Cultural Cognition Project. “People predictably and justifiably weigh whatever you tell them against what they think your objective is. In every interesting case of public policy making, the judgment of what is the best available evidence, and what are the implications of this evidence, is a subjective, nonscientific, value-based decision. It’s true that the public doesn’t know the scientific details of divisive issues such as climate change. But it doesn’t follow that the reason they’re divided is because they don’t know the details.”

Kahan’s research suggests conflicts about scientific findings are more a product of our different identities than different levels of scientific literacy. Not surprisingly, he found that people with different cultural values strongly disagree about how serious a threat climate change is, and draw radically divergent conclusions from the same evidence. Interestingly, however, he also found that individuals who are the most science literate and the most proficient at technical reasoning are also the most culturally polarized.

In a recent Nature column titled, “Why We Are Poles Apart on Climate Change,” Kahan concluded that the problem isn’t the public’s reasoning capacity, but rather a toxic partisan environment that says, “believe this; otherwise, we’ll know you are one of them.” He argues that people who adopt a position that runs counter to their cultural group “risk being labeled weird and obnoxious in the eyes of those on whom they depend for social and financial support.” In the end, tribal affinities trump any and all evidence.

“It would be a lot more constructive if we could argue about values instead of the facts,” Kahan told me, “because then we wouldn’t be calling each other anti-science and stupid.”

Sarewitz drew a parallel conclusion: “If you say the facts are consistent with a particular position, and that you believe in this position because of those facts, then you are forcing an argument over the facts, even though what really matters is the underlying reason for your preference, the motivating values and worldviews. Somehow we seem to think that the facts make our values stronger, but that’s backwards. People may find other facts, but they can’t tell you what to believe.”

The implications for environmentalists should be obvious: By themselves, fact-driven arguments don’t work very well. To be perfectly clear: I’m not disappearing down a postmodern rabbit hole or arguing for some kind of cynical “post-truth” politics in which partisans can say whatever they want. Facts matter; evidence is important. But we in the environmental movement need to recognize the limits of our appeals to science and reason.

Meanwhile, back in Transylvania County, the campaign against the biomass plant just kept getting bigger and stronger. Its growth was due, in part, to the organizers’ instinctive move to employ the kinds of strategies suggested by Kahan and Sarewitz – to frame a contest about values instead of having a competition over facts.

“People were coming at this from a lot of different angles, so we agreed up front to take an inclusive, holistic, nonjudgmental approach,” Ned Doyle, one of founding members of People for Clean Mountains, told me. “We also decided that we didn’t just want to say ‘no.’ So we organized public venues for sharing and promoting alternative ideas for sustainable economic development and job creation in this county.”

The strategy seemed to be working. My elderly neighbor – who has a Sarah Palin sticker on his truck – called me one day to ask how he could help “stop that biomass plant from ruining our natural environment.” PCM’s “Burning Biomass is Nuts” signs, featuring Transylvania County’s iconic white squirrel wearing a gas mask, began sprouting up everywhere.

But following Sarewitz’s suggestion – “Don’t use science to try to solve political problems, but rather try to solve political problems first.” – is not always easy. Because we kept mistaking a political conflict for a technical problem, we futilely attempted to resolve the controversy with science. We spent a lot of time and energy arguing over technical details of the proposed biomass plant, such as the relationship between pyrolysis and incineration. To support their respective positions, each side stridently cited an impressive web of peer-reviewed scientific papers. They converted no one.

We probably would have been far better served by having respectful dialogues about the more fundamental, non-scientific issues surrounding the project, such as our different visions for how best to lift ourselves out of our post-industrial economic malaise. Perhaps this would have enabled us to find enough common ground to work together. Maybe we even could have tinkered with the original biomass proposal until we found a way to make it work for both sides.

That didn’t happen – or at least it hasn’t yet. In July, in front of a packed crowd at the county courthouse, our commissioners voted 3-2 to approve a PCM-driven moratorium preventing county approval of any biomass electricity-generating facility for the next 12 months. The project, however, is not gone for good. Two of the commissioners who voted in favor of the moratorium made it clear they did not necessarily want to stop this project, but simply wanted more time to consider it. Before making a decision, the commissioners said, they would like additional scientific information.

Robert Cabin is an associate professor of environmental science and ecology at Brevard College. He is the author of Intelligent Tinkering: Bridging the Gap Between Science and Practice and Restoring Paradise: Rethinking and Rebuilding Nature in Hawai‘i.

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

DonateGet four issues of the magazine at the discounted rate of $20.