In April 2006, 32-year-old Jason Chellew was relaxing in his Alta, California home when the ground opened up beneath him, swallowing him and most of his living room. It sounds like fiction, but what happened to Chellew was actually the last chapter in a series of historical events that started with the Marshall Gold Discovery on January 24, 1848, and ended when an old gold mine collapsed beneath Chellew's home, taking his life. The incident rattled a lot of Californians, who are mostly brought up to feel proud of the state’s colorful gold mining history. No one likes to think that history is hazardous, but in California it’s becoming increasingly difficult to hide from the real, if belated, consequences of the Gold Rush.

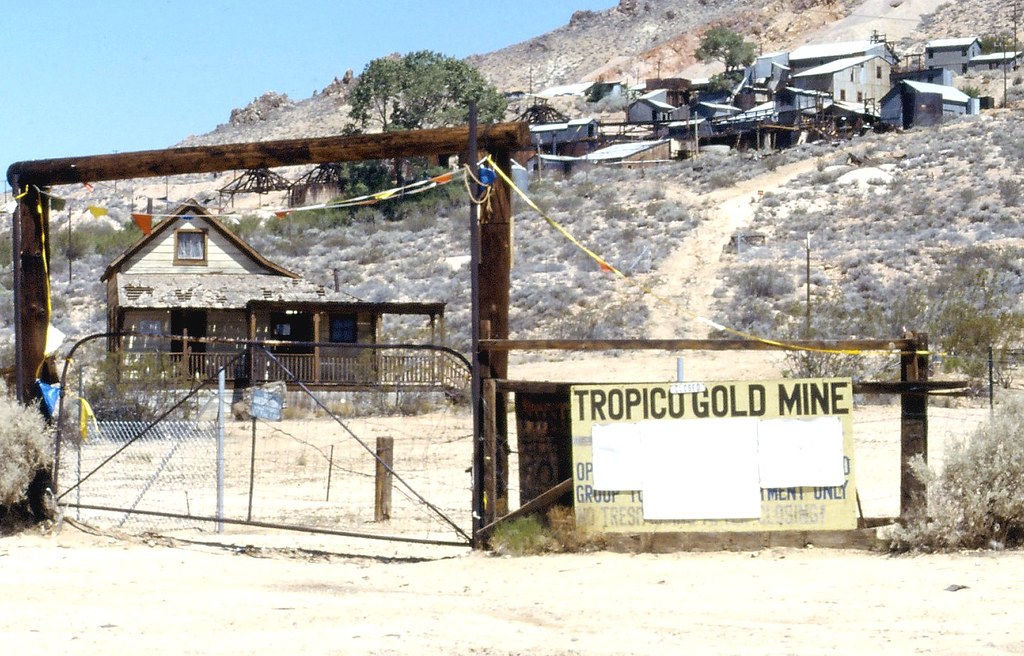

The Bureau of Land Management estimates that there are 47,000 abandoned mines in California —mostly in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Klamath Mountain regions of Northern California and the Mojave and Colorado Desert regions in Southern California — but no one really knows the exact number. Many mines were never recorded or mapped, and they could be anywhere — under any home or business, abandoned but covertly menacing. And collapsing mines aren’t the only threat. Mining-related chemicals like lead, mercury, and arsenic are still hanging around in the soil and water in these areas, and the process of removing those chemicals is complex and expensive.

Michelle Fuller is the Water Treatment Operator at the Empire Mine State Historic Park in Grass Valley. She works on the Magenta Drain Passive Mine Water Treatment System, which was installed in 2011 to help the park address the problem of contaminants in the water — water that comes directly from abandoned, flooded underground tunnels. Fuller is a champion of the system, pointing out its components with enthusiasm, as if admiring a water sculpture instead of a series of plastic pipes and conduits.

The Empire Mine was once the most productive hardrock gold mine in the state — today it’s a popular recreational destination. The locals bike, hike, and ride horses on the 856-acre park’s 14 miles of trails. Couples get married on the lawn in front of the Cotswold-style “Empire Cottage,” the ridiculously named two-story estate house made of stone and redwood. In the mine yard, visitors can peer into the gaping mouth of the old mine shaft, which vanishes into impenetrable darkness, beyond which lies 367 miles of tunnels.

The Empire Mine was a functioning gold mine from the Gold Rush through the 1950s. Arsenic occurs naturally in the wall rock and gold ore, and gold mining operations released the dangerous chemical into the waste rock and mine tailings (the debris that remains after the sediment has been picked over by miners). No one pulls gold out of the Empire Mine anymore, but chemicals from past mining activity still linger in the water and soil. In 2007, park officials discovered arsenic in the park's soils. When bikers and joggers kick up arsenic-containing dust on the dirt paths, it can become airborne, and that can pose a potential health hazard to park visitors. To make the trails safe again, Fuller says the arsenic hotspots were covered with natural material, but even that presented a problem — the material had to be obtained from outside the local area, because most of the rock and soil that could be purchased locally also had roots in California’s gold mining past, and it often contained more arsenic than the hotspots did.

The arsenic settles into the water table, too. Many of the mine’s lower tunnels are flooded, and during periods of heavy rain the water rises and leaves the mine, entering the above-ground water system. “The water I have coming through here,” Fuller says, pointing to what looks like clear, drinkable water, “that’s not groundwater, that’s mine water.”

Fuller and her team make sure that the water is clean when it leaves the park — the Magenta Drain is a chemical-free system of pumps, settling ponds, and wetlands. But the entire region outside of the park’s boundaries is subject to the same or similar mining-related contaminants. North of the Empire Mine is an old hydraulic mining area called Malakoff Diggins — also a state park. Its central feature is a high canyon wall that looks like it belongs in another part of the solar system. Malakoff’s brightly colored ponds and otherworldly geography are evidence of a sinister history — the canyon wall exists because half the mountain was washed away by the high-pressure jets of water miners used to release ore-containing sediment, and the ponds bear evidence of the chemicals that helped miners retrieve gold from that sediment. “All those ponds up there are emerald blue,” says Fuller. “The miners used a lot of mercury up there. That’s why it’s all blue.”

Mercury gets into the ground, too, and is absorbed by the vegetation. A 2007 study by the National Center for Atmospheric Research found that wildfires are a significant source of airborne mercury pollution. When dry, mercury-laden vegetation burns, the mercury becomes airborne and ends up in the atmosphere, where it remains until precipitation delivers it into the waterways. As California experiences longer periods of climate change-related drought, frequent wildfires, and the mercury contamination that goes along with them, will only become a more significant problem.

This pattern of mining-related environmental risk can be seen all over the nation — in 2015, Environmental Protection Agency workers investigating water levels at the 130-year-old Gold King Mine in Colorado’s San Juan mountains inadvertently released 1 million gallons of contaminated wastewater into the Animas River, turning it a bright, toxic, mustard-yellow. Crews later confirmed that lead levels in the polluted waters were 100 times higher than what is considered safe, but lead isn’t the only heavy metal in the spill — there’s also arsenic, zinc, and copper. EPA officials say they plan to take tissue samples from deer to help them assess the actual damage to the region’s wildlife population.

And then there are the sinkholes — rare, but still troubling. After a period of heavy rains in January of 2017, a sinkhole opened up behind a Grass Valley car dealership. Seven stories deep and 80-feet in diameter, the official cause was the failure of a seven-and-a-half foot underground culvert, but plenty of residents thought there might be more to it than officials were letting on. Social media was full of speculation that the sinkhole was caused by a collapsed mine shaft, and with thousands of unmapped mines lurking underground, that's a pretty ominous theory.

Whatever the cause, sinkholes like these are a grim foreshadowing for what is certain to be a tumultuous future for California, which is expected to see longer, more devastating droughts followed by periods of heavy rains and flooding. Much of California’s gold mining history still lurks beneath the surface, and while cleanup efforts like the Magenta Drain are critical initiatives, they only occur in known problem areas like the Empire Mine — leaving thousands of underground mines to linger in toxic anonymity.

The settling pond that is the heart of the Magenta Drain system is almost picturesque, with a fountain of water in the center and a pair of black and gray Canadian geese floating on the surface, oblivious to the heavy metals settling beneath them. The system is an impressive piece of engineering, but in the context of the whole state of California, it’s a little bit like trying rebuild a war-torn city with one hammer and a handful of nails.

Fuller is clearly proud of the system’s success, but even she acknowledges that it’s just one small fix in an otherwise enormous statewide problem. The Gold Rush’s footprint is broad, and the chemicals that linger in the ground call everything into question, even the safety of eating wild blackberries and the figs that grow in places with roots in California's gold mining past. “The list goes on and on,” she says. “The miners left a mess behind all over California. It will take a lot to clean it all up.”

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

Donate